What would you like to know about the French system of education?

Here’s a brief description for you of its background, its structure, and some of its important characteristics, just as an introduction.

French education, like that in other countries, is struggling greatly to cope with the current pandemic. Its functioning is in enormous upheaval. Its very remaining open is problematic and controversial, and organization of instruction in safe conditions is an ongoing challenge. The information in this article describes the system as it operates under normal circumstances (which may be a long time in returning) but it should help nevertheless to understand the underlying nature of the system.

You should know that in its organization and administration, the French system of education is very different from that of the U.S. and of some other English-speaking countries. It provides a striking contrast for Americans, who have no centralized Ministry of Education, but rather 16,800 or so basically autonomous school districts run by locally elected school boards, and even differing regulations from state to state. The centralized French approach to education stems, of course, from a long overall tradition of centralized government, and was designed to ensure at least égalité to French citizens by providing free, universal instruction accessible to all.

In France, the centralized public school system is under the supervision of the Ministry of National Education, Youth, and Sports. It is for all intents and purposes the same everywhere, including overseas, except for minor differences due to local conditions or constraints. There is a national curriculum with national exams. Teachers must obtain national certification, and belong to a national corps of civil servants.

Like other educational systems in the developed world, the French system has of course to cope with a number of concerns, including the very serious problems of violence and substance abuse in some schools, problematic math and reading levels, teacher training and absenteeism, and the competition with the internet, phones, and TV for students’ interest and time.

There is concern about anxiety and depression among students. There are naturally periodic complaints about all these issues, and calls for reform of various kinds which successive Ministers of Education have tried to deal with, with varying success.

Nevertheless, you will see that the French system has an intellectual and educational tradition of quality and high standards, of which the country is generally proud. Its graduates are highly regarded throughout the world.

16 Key Characteristics of the French Educational System

- Most notably, its extreme centralization with national curricula, exams, and corps of civil servant teachers, plus inspectors.

- Longer school days and more vacation days than in most other European countries. The total number of school hours in the year is, however, roughly the same.

- The stress on the secular character of public education, a principle held very strongly by government and educational authorities. This has, for example, led to a national problem concerning the wearing of a Muslim head veil to school, which has been basically forbidden by authorities. The argument is that all conspicuous apparel of a religious nature ought not to have any place in the secular schools where everyone should be equal and neutral. There is a refusal of what they call communitarisme, or the juxtaposition and delineated coexistence of identifiable ethnic or religious communities, as in the US.

- The importance of education to the French public. The bac is a sacred institution, a matter of public interest. The press covers the topic extensively, and the actual exam questions are announced to the public nationwide after the exams. In late August and early September, the whole country prepares for the Rentrée Scolaire, with considerable press and TV time devoted to the return of the country’s youngsters to school.

- An emphasis on abstract thought. The French primary curriculum tends to deal with abstract concepts in math and grammar sooner than in other countries. The four hour-long bac essays in French and philosophy ask abstract questions like, “Can philosophy get along without a reflection on science? Or “Is human freedom limited by the necessity to work?” or “How does one recognize that an event is historic?” (These are actual philosophy bac questions.)

- A tradition of the transmission of knowledge, the cerebral duty of teachers to instruct, not educate in the most comprehensive sense. In connection with this, secondary teachers mostly come to school for their 16-18 hours of class, but do not have to be in school otherwise. Monitoring of halls, classes, cafeterias, and recreation areas is done by surveillants hired expressly for that purpose, since it is not considered part of a secondary teacher’s job.

- A relatively elitist approach, and accompanying this, a tendency toward individual competition and achievement. One of the areas where teaching practice has evolved most in the last couple of decades is the inclusion of small group work and team projects to teach students how to work together cooperatively.

- Early orientation at the end of the ninth year into the type of study a student will follow, as contrasted with the American system, in any case, when this is still the beginning of high school and choices remain open.

- A tradition of rigor and clear thought in presentation of ideas. A noted French philosopher Alain, said, “L’homme se forme par la peine”, that is, “man is formed through effort” and this idea has always been present in French educational circles. Learning is not generally expected to be fun.

- A certain reliance on rote learning and lectures, despite much change in teaching practice in general. One of the areas where teaching practice has evolved most in the last couple of decades is the inclusion of small group work and team projects to teach students how to work together cooperatively.

- A generally large number of subjects studied, at all levels of schooling, and relatively few options as opposed to compulsory subjects, especially for the bac. The role of math is especially important in French education and is the fundamental means of selection of the best students.

- Relatively short shrift given to the arts, except when chosen as an optional subject in the lycée. Students may get only an hour a week of music or art in early secondary school, and none later. The existence of the outside network of arts possibilities means that those who have the interest and the means tend to pursue the arts outside of the school setting.

- Sports practiced outside of school in community teams rather than school ones. Sports are available to varying degrees to French students, but this is definitely not a sports-oriented educational culture.

- A marking scale from 1-20. The passing mark is 10, thus a little lower than in other marking systems.

- Absolute marking standards, making it possible to have a whole physics class with marks below the necessary required average and severe marking practices. Giving low grades is sometimes considered to be a way of motivating students to do better. Corrigés, or corrected answer sheets, are often given out after exams, including literature essays, to indicate what should have been the answers or key points treated.

- Several parents’ associations with links to major political factions. Sometimes representatives of several associations attend the same class council meetings.

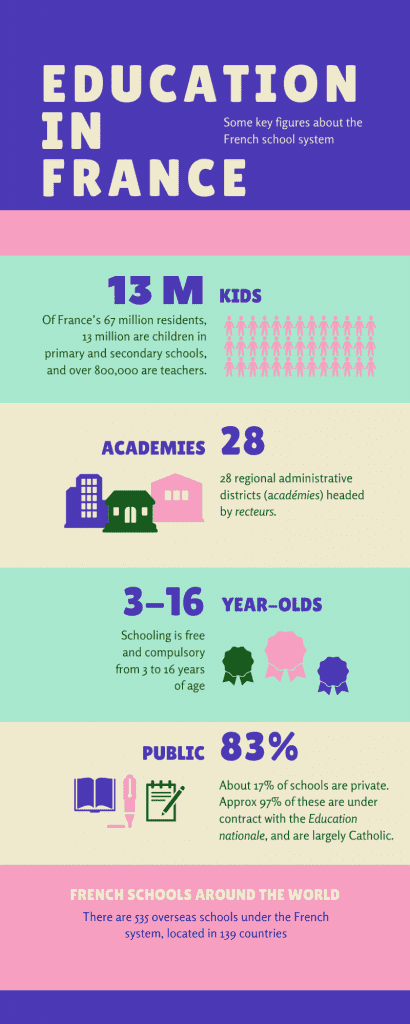

Key figures:

- 535 overseas schools under the French system, located in 139 countries.

- 28 regional administrative districts (Academies) headed by Recteurs

- Schooling is free and compulsory from 3 to 16 years of age.

- Of France’s 67 million residents, 13 million are children in primary and secondary schools, and over 800,000 are teachers.

- About 17% of schools are private.

- Approximately 97% of these private schools are under contract (contrat d’état) with the Education Nationale, which requires that their school programs be identical to those in the public system, in exchange for a substantial subsidy. These schools are largely Catholic.

Nancy Willard-Magaud holds degrees from Wellesley College and Yale University. Formerly Director of the American Section of the Lycée International de St. Germain-en Laye, she helped to create the American Option of the French Baccalauréat (OIB) and served as its Inspectrice Générale Déléguée (head moderator). Her three sons attended French schools and American and French universities. She has been awarded the Palmes Académiques for her service to French education and culture and is currently special consultant to the English-Language Association of France (ELSA-France).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!