Our Beginnings

It All Started with a Question – Are our Children American?

It all started back in 1961, when Phyllis Michaux, an American woman married to a Frenchman and living in France since 1946, found a friend in a similar situation. They began talking about the future of their children, their American and French citizenship and wondered whether there were other women “out there” in a similar position.They had a question and an idea. The question was, “How many people are affected by the citizenship law 301(b)?” At the time, under section 301(b) of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1960, children born overseas of one American parent would lose their American citizenship unless they lived five consecutive years in the United States between the ages of fourteen and twenty-eight. Essentially, the children would have to move to the United States sometime before their twenty-third birthday to retain their American citizenship. The idea was to find out how many families were affected. This they did. And they did a lot more along the way.

Phyllis and her friend drew up a questionnaire to be given to as many other American women as they could find. They put an ad in the Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune calling for a meeting at the American Church in Paris.

Living Room Meeting

About 15 women came to the meeting. A group of those women decided to form a club. They set up a meeting for the month of May and needed a place to hold it. While walking down Avenue Franklin Roosevelt, Phyllis Michaux walked by a building with a sign reading “Club France-Amériques.” She wandered in, ran into the manager in the lobby and explained the situation. The manager agreed to give the group a room.

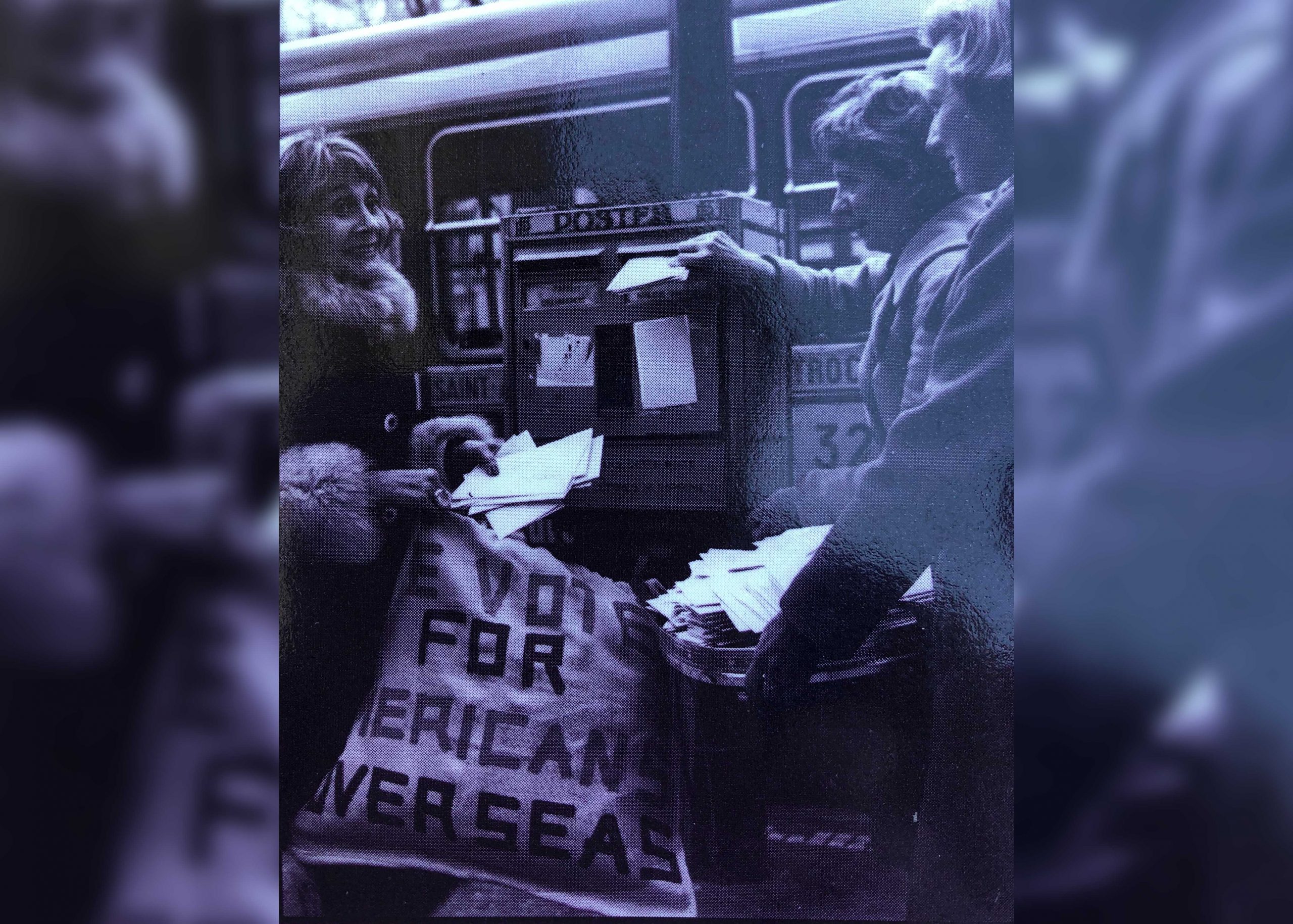

Making Our Voices Heard

That summer Phyllis Michaux went to Washington DC and visited the State Department to inform them about the new group. The effort paid off, and in the fall, the then head of the former U.S. government department, the United States Information Agency (USIA) was AAWE’s first luncheon speaker. All the women in attendance at the luncheon were put on a list to receive information and documents about the United States to pass on to French family and friends.

In October, an article about AAWE appeared in the Tribune — at the end it said to call Mrs. Raoul Michaux for information. And there were plenty of phone calls! About 50 women met — almost none of them knew each other, and some of them were quite isolated. One woman took a map of Paris, pinpointed their addresses and began neighborhood gatherings over tea.

Building a Foundation

That first year, from April 1961 to the summer of 1962, the women at AAWE prepared the foundation for the club. A declaration of association was made at the Préfecture; Gertrude de Gallaix wrote up a constitution and in Phyllis Michaux’s words “tried to keep me in line from making too many mistakes.”

AAWE received the Head of the Passport Office and issued the first paper on citizenship laws. One member created a panel on bilingualism. The association held Christmas and Halloween parties for children, and a party with their spouses. However, one of the most rewarding activities was just getting the women together. Previously isolated, they had found a sense of community.

AAWE in Action

The women of AAWE didn’t stop there. That initial question about the Nationality Act was still unanswered. In early 1961, Phyllis Michaux read a Washington Post article about a court decision on the 301(b) section. An Italian American had challenged the law and won in a district court, which declared the residence provision unconstitutional. However, it was noted that they were, “aware of the considerable danger that children born and reared abroad, schooled where English is not taught, celebrating foreign holidays with the family of the non-American parent, will have no meaningful connections with the U.S., its culture or heritage.”

This was the perfect opportunity for AAWE to prove the contrary. From there, letters were written, lawyers were enlisted, and the project went from an idea to a co-filed amicus brief with the American Bar Association. AAWE contributions financed the legal fees, and although the case was lost in the Supreme Court, an amendment to the law was proposed in Congress.

With more determination, the help of an attorney, and a letter-writing campaign, the residence period was decreased from five to two years.

In the end, it was the ideas of AAWE which came before the Supreme Court, and in Phyllis Michaux’s words, “It is really amazing what you can do with nonprofit organization work. Never let yourself be put down because you belong to a women’s club.”

AAWE has continued this work and expanded it over the years to this day.